Effective or Stimulating Repetitions

Research has long suggested that the dominant mechanism for muscle growth is mechanical tension. Mechanical tension is a localized stress within the cross-bridges of muscle fibres. It can't be seen, it can only be inferred.

It can be inferred in one of two ways:

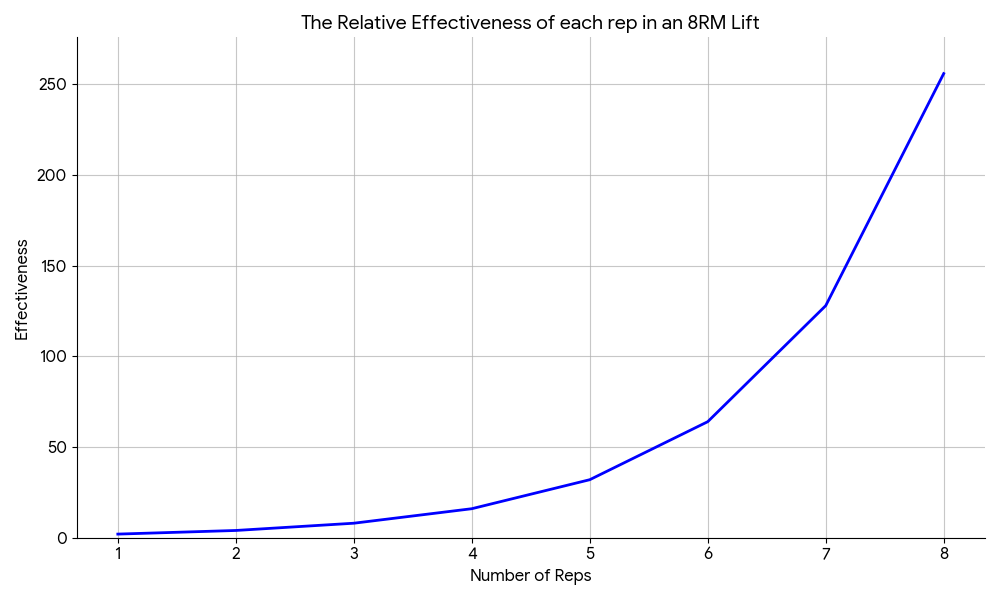

1) Using a resistance representing ~80-85% of the maximum resistance. This represents a weight that can be lifted ~5-8 times before task failure. Training done with this level of resistance leads to full muscle activation on rep 1 of any given set.

2) Training to the point of momentary muscle failure using a resistance > 30-40% of maximum. This can represent any exercise lifted upwards of 25 (maybe 30) times before hitting task failure. The final (possibly) ~3-8 reps (I typically just say 5) under these conditions lead to full recruitment. The more reps you do, the more important hitting failure becomes.

The reps completed under these conditions are often called the stimulating repetitions or the effective repetitions. If you're training for growth, it is important to understand these thresholds so that your training can appropriately stimulate muscle hypertrophy.

This is not a new concept by any means.

Arnold Schwarzenegger mentions the idea briefly in the documentary Pumping Iron way back in 1977. And I've read references to something similar written long before then. Although I think it was often improperly used as a way to justify chasing "the pump." Which, for the record, doesn't matter; that's just localized swelling.

Here he states that it's the last 2 or 3 or 4 reps of a set ... (TBD)

Only now the mechanistic research appears to be catching up. Not that we have direct evidence of its existence, but it's the only current theory that rationally explains why:

- Sets of 8, 10, 12, 15, 20, and even 25 (possibly 30) can generate the same amount of hypertrophy when the training is taken to task failure

- People lifting for very few (<5) repetitions but with high resistance, far from failure, don't seem to get as big as those doing moderate-load bodybuilding-style training.

- They are improving strength, often with low training volumes, far from failure, not accumulating enough stimulating repetitions over time. At the very least, it's slower, and the adaptations are more neural.

- Total repetitions completed in a training session or per muscle don't matter (at least in isolation)

- For example, 2 sets of 25 are not as effective for growth as 5 sets of 10, despite both being 50 reps completed. The former is likely only ~10 effective reps, while the latter is ~25.

- Rest-pause training can be about as effective as straight set training, and more time efficient.

- The fatigue and short rest are still capable of hitting the recruitment threshold under the right conditions, even if you have to chip away more (e.g. 3-5 rest pause sets ≅ 2-3 straight sets)

- The traditional approach of trying to do the same number of reps for all sets of an exercise might not be great for growth

- You leave effective reps on the table in the earlier sets so that you can still hit the required reps in subsequent sets. As a result, only the last set or two is yielding many stimulating repetitions (this is why descending pyramid training has long been a staple approach in bodybuilding)

- Purposefully slowing down repetition speed doesn't cause additional hypertrophy (the slowdown has to be involuntary)

- Occlusion (blood pressure cuff) training seems to generate growth (at least in beginners) without achieving failure, even at higher than 25 repetitions.

- It appears that the lack of blood supply can create metabolic conditions for mechanical tension, even when not approaching failure

- Although I'd argue it only works for the limbs, and it's extremely uncomfortable to do, making it impractical all the same.

- It is so hard to build muscle using exclusively calisthenic training

- It's hard to push yourself to failure for such high repetitions (especially when your capacity creeps over that 25 or so rep threshold), and you're probably quitting for metabolic reasons (e.g. being out of breath) long before they can create the necessary localized muscle stress

So today we’re going to talk about a theory that helps explain all of these things while also providing you with an important framework when you’re trying to gain muscle with resistance training.

Proximity to Failure

Research has largely shown that training to failure with high reps and training to failure with low reps yields similar results in hypertrophy.

What’s the common theme?

Training to Failure! Or at least a high proximity to failure.

Put a different way, the accumulation of fatigue leads to bigger and bigger motor units being recruited, which in turn creates enough mechanical stress to yield a growth adaptation.

Henneman’s size principle tells us that a muscle is activated in ascending size. It’s a key principle in the science of muscle hypertrophy.

Smaller motor units are engaged first, and then bigger units kick in as you fatigue. In essence, the same large motor units (and muscle fibres) within a muscle will be engaged whether you lift 3 sets of 5 reps to the same proximity to failure or 3 sets of 15 reps to a similar proximity to failure.

Henneman's size principle explains how you get maximum recruitment even with lighter loads, so long as you fatigue a muscle to a certain level or you use a heavy weight in that 80-85% of maximum capacity (for 1 rep, or 1 rep max).

That means you should train to failure, right?

Yes and no.

It depends on:

- The goal of the training

- Remember, the concept of stimulating repetitions applies to growth adaptations

- The intensity of the exercise

- If you can only complete 8 reps of something or fewer, you probably don't have to train until you can't complete another (concentric) contraction. Stopping short of failure in this rep range will likely yield a similar result to failure training in lower intensity (higher repetition) ranges

- So long as you're finishing at least 4-6 reps of a possible 8 (which is about 2-4 reps in reserve [RIR])

- However, your body structure might also not tolerate higher ≤8 rep intensities for long durations of time, and there are other benefits to higher and lower rep ranges to be considered

- I suspect that something that would cause failure before ~12 reps (maybe ~15) requires getting within 1-2 reps in reserve [RIR], and anything higher than that most likely needs to be taken right to failure to cause similar growth

- If you can only complete 8 reps of something or fewer, you probably don't have to train until you can't complete another (concentric) contraction. Stopping short of failure in this rep range will likely yield a similar result to failure training in lower intensity (higher repetition) ranges

- The exercise chosen

- Taking squats, deadlifts, bench press and other higher technical requirement exercises to failure is ill-advised

- Compound lifts might result in more systemic fatigue from training to failure than localized fatigue, and therefore likely benefit from higher resistance rep ranges (≤8 reps)

- The frequency of your training

- Want to train a muscle group 3x a week? Training to failure probably isn't a good idea.

- Want to train a muscle group 1x a week? You likely have to train to failure.

- The volume of your training

- Doing less than 5 sets per muscle group in a session? You likely need to train to failure more.

- Doing 10 sets per muscle in a session? You might want to avoid training to failure more

- The exercise order and any potential competing priorities

- If growth isn't your primary objective and it's merely a part of your strength or performance routine, you need to be careful in how training to failure is applied

- Your personality/natural training tendencies

- Some people don't know how to do anything but push themselves to their limits, but they run into trouble because they run into them at high volumes.

- Others may not want to, or like to, push themselves hard, and they will have to make up the difference with additional or high training volumes

- Most people are between those 2 extremes

Finding the "Right" proximity to failure

The appropriate proximity to failure, most of the time (in my experience), is reaching what has historically been termed "technical failure."

The way most people describe that is a tad ambiguous, though, so I want to be explicit in how I define it. Technical failure is achieved when movement speed has involuntarily and meaningfully slowed.

It has to be an involuntary "real" slowdown in capability resulting from fatigue to indicate the reps will be stimulating, and mechanical tension is being created.

In many lifts, it manifests itself as a hitch. A hitch is when you reach a struggle point through the regular range of motion in a lift, and the natural flow of the movement seems to momentarily stop. It might take you a second (or two!) to push through what is often the sticking point in a movement.

A sticking point is a point in a dynamically loaded movement where leverage is often at its worst and/or the individual is weakest. Very often, these are quite predictable. For example, roughly the mid-way point on the way up during a pull-up, deadlift, squat or bench press. Very often, people can get a weight moving from the bottom (or they use momentum), but they hit that mid-point and have to grind through.

For growth, some grinding is probably a good idea. For strength or power, not so much, but that's another topic for another discussion.

Now, hitting this point of involuntary slowdown, grinding or hitching a lift will bring you within about one or two reps of failure in most instances. Meaning you'll be able to finish the rep you're on and maybe one or two more at best, before you'd fail to finish that last rep.

However ...

- Not all exercises require this approach

- Not everyone is good at gauging this involuntary slowdown

- Not everyone is training with enough volume to benefit from this approach

- Not everyone is using a rep range that benefits from this approach

Exercise Selection

I reason I prefer this approach is that few of my clients have access to many, if any, machines and will end up doing more compound lifting than is potentially ideal for pure growth goals. I don't work with professional or elite bodybuilders, but I've had a few amateurs over the years.

In our gym, we have a leg extension/curl combo machine and a big dual cable machine, but that's about it. I'd love it if we had a few more, maybe, but we just don't have the floor space. Many of my online clients are training out of home gyms or have access to boutique gyms with minimal machine equipment.

I don't normally subscribe to the idea of "machines = safer training," but in the context of training to failure, it's probably true. Maybe? To be clear, I've been told this for ages, as far back as any exercise physiology class I took, but I've never seen or read a research paper looking into this. Near as I can tell it's a game of telephone (aka hearsay) and assumptions about what constitutes "safe training."

Anecdotally, most of the gym injuries I've seen happen in person have been with relatively light, basically warm-up weights and occasionally a PR attempt. It's rare to see injuries result from typically moderate rep ranges used for growth goals.

Regardless of any potential safety reasons, the bigger reason to avoid failure is typically practicality. If you can't finish a concentric bench press or squat exercise in a rack, you either need a spotter (or two!) or you have to dump the weight on the pins. If you have to dump the weight, you probably have to strip it and get it back to the starting position.

If you had to do that for every set, training would take forever!

If you're on a 45° sled leg press or a hack squat or a pendulum squat or a Smith machine squat or whatever, I'm not sure that the stripping and reloading problem goes away entirely. But you can at least kind of rack it wherever it lands with the safety mechanism, so at least trying to get it back to the starting position will be easier? Maybe you don't have to strip off quite as much? I dunno ...

Big picture?

Training compound lifts to failure on all sets where the weight is lowered first is a bad idea. Training them to failure where the weight is lifted first is less problematic, but be careful with anything involving your low back or shoulders (those tend to be two of the most problematic areas, sometimes knees).

For isolation exercises, I'm less sure any of that matters, regardless of the tool. The weights are lower, the movements are smaller, and getting out of trouble is just easier with these. Starting where you left off after failing also isn't much of a concern, so you could train these to failure far more easily.

Not Good At Gauging Fatigue?

I've tried to make my definition of technical failure as objective as possible. The problem is that some people start slowing down in certain exercises far from failure, and based on experience with other lifts, they might be inclined to quit voluntarily.

But what they might not realize is that their experience with that lift is different and possibly unique. I'm not saying it is, and if you challenge yourself to failure periodically in exercises (or similar exercises) it can help you understand how your technique adjusts to fatigue and ultimately fails.

Sometimes you need to run some experiments on yourself in this regard. This might mean you have to test an exercise to failure periodically. I'm not saying you should do this often, for all exercises and all sets.

What I'd recommend is that if you're struggling to make good progress on certain lifts, or if you're unsure about your relative proximity to failure; Attempt to train the offending lift to failure on the last set. Every once and a while. This could be once a quarter, or a couple of times per year, depending on the person, or never if you're pretty good at it and aren't running into any problems. You're doing this just to challenge your own assumptions about your own training. Are you as close to failure (e.g. within 1-2 reps of it) as you think you are?

Well, only one way to find out! You have to test the theory sometimes, just to see where failure is on some of these lifts. That said, see the relevant point above. I doubt most people will struggle with failure on most isolation lifts because they can lift right to it with relative ease. They won't be cardiovascularly gassed trying to do it, so they can probably maintain the distinction between feeling tired systemically and being incapable of another rep locally.

It's the compound lifts that people tend to assume are hitting the target muscle that might not be (for other reasons) that tend to warrant this type of approach every now and then. But again, if you're training these in my recommended range (if it's possible, sometimes it's not) of 5-8, failure doesn't matter, only lifting a decent number of reps for stimulation. Here, the test might become determining if you can lift the weight 8 times before failing.

Doing it on the last set is good because you were going to strip the barbell or plate-loaded machine probably anyway.

Training Volume Considerations

If you're only doing one or two hard sets in a given workout per exercise, and that's the plan for the foreseeable future, training to failure might be more of a hard requirement.

Which isn't to say you'd get nowhere with my recommendation above, but it'd probably be a lot slower. It's already painfully slow when you're doing things well.

If you're doing that at low training frequencies like 1x/week, then training to failure is an even bigger requirement. After all, you're giving your muscles a week to recover anyway.

You want to consider total weekly training volumes. Typically or conventionally, the sweet spot is thought to be 10-20 sets per muscle group per week. I usually tell people 9-16, but I also usually get people a little closer to failure, and I'd rather start with less and work up than the reverse. If you can accomplish what you want to accomplish with 10 sets a week, why do more?

Conversely, some people can't get to that threshold, so they need to make up to it with higher proximity to failure. Or they like doing substantially more volume than that (e.g. 20+), and there is simply no way you can recover from all that failure training at those volumes. So this is a variable to understand in the other popular training mix, at least when it comes to growing muscle.

Training Intensity Considerations

I already touched on this pretty heavily. If the intensity is under 8 repetition maximum (8RM), then training to failure doesn't do much of anything extra because you're already getting maximal recruitment on repetition 1.

The more problematic scenario is when you're above that threshold. Up to about 12 reps, I think my technical failure (involuntary concentric slowing) probably still holds true, but the further you get from there failure becomes far more important.

Summary on Failure

The state that I'm trying to help you find is a stressor that's "just right" for you.

And I probably didn't hit all the relevant points there but the point is there will be little self-experimentation involved in discovering where the exercises in your routine are delivering an appropriate stimulus.

If something isn't growing or the proxy for growth (weight in a moderate rep range) isn't going up the way you can expect, this could be a problem you didn't account for. It might be the training volume or intensity or exercise selection but it could also be the proximity to failure of your training.

How Many Effective Reps Are There Per Set?

You're going to hate this ...

But it depends ...

I actually have no idea, only a broad guess based on some of the assumptions you already read above.

- Maximum Muscle Fibre Recruitment is observed at approximately 80-85% of the self-experimentation1 repetition maximum.

- This correlates with 5-8 reps, so theoretically it could be as high as 8 if you get maximum recruitment on rep 1 under these conditions.

- Training within 3-5 reps of failure appears to generate some (although sometimes worse) growth outcomes

- I think this is volume-dependent, and the research on these rarely (if ever) used an objective measure for reps from failure like velocity (bar speed, whatever)

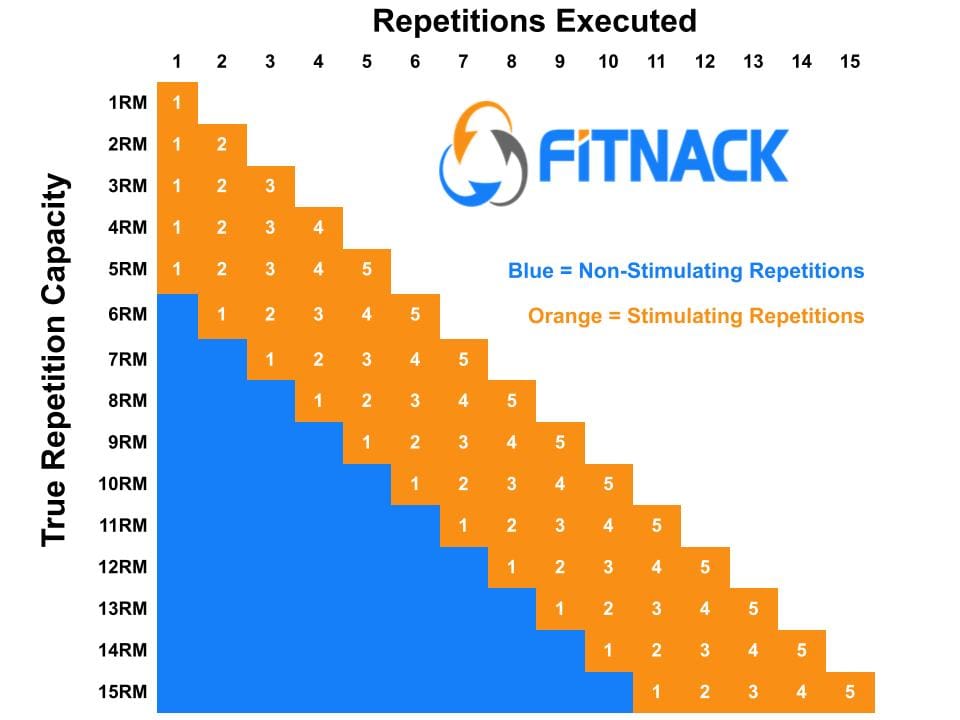

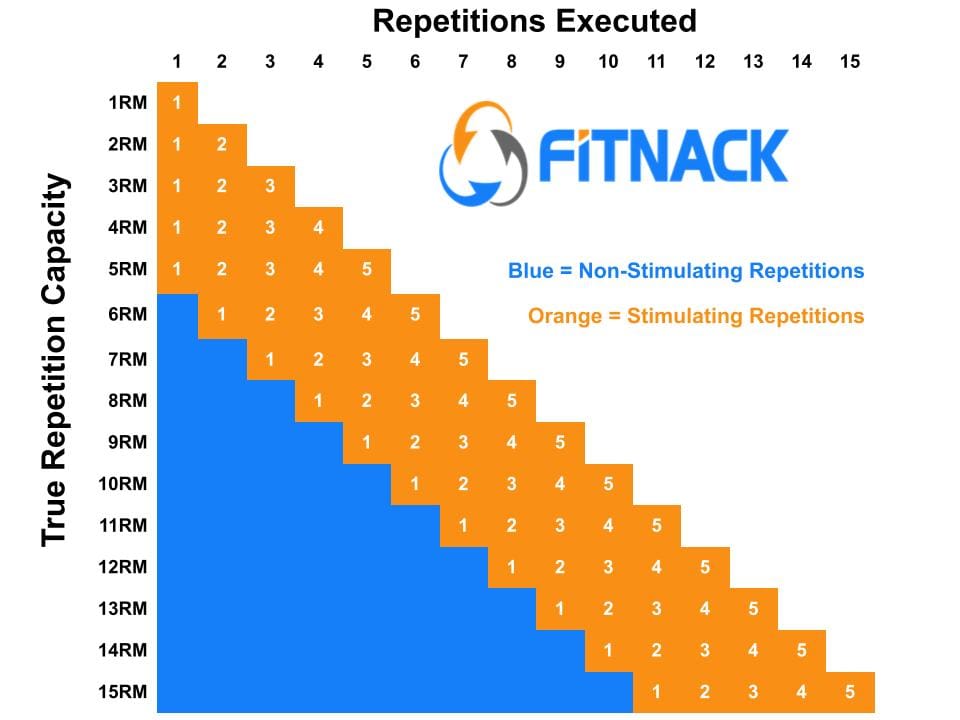

I know I used this image as the header image in this post, but it's just my best guess +- 3 reps:

5 seems about right in a straight set context, but ...

It could be 8 if the 8RM idea is correct? Or maybe it's only 2 or 3 like Arnie said above?

Maybe it looks more like this?

Maybe the closer you get to failure, the more effective that rep is at stimulating growth based on the mechanical tension is causes? Each rep closer to failure might be more effective? I don't know ...

I suspect reps are less effective in subsequent sets of a given exercise, too. Meaning you might take set one a rep or two shy of failure, to let's say 6 reps with an 8RM load. You repeat that task in a few minutes, and you do 5 reps, now you adjust the weight down a bit to keep it closer to 6, and on set 3, you do 6 or even 7 reps.

This is a practical example, so the weight is being adjusted to fit the desired outcome. Now, were the 6th and 7th reps on set 3 as effective as reps 4 and 5 in set 2, or the 5th and 6th reps on set 1?

Somehow (call it a gut feeling), I suspect no. That's based on tangential research and just the variation I've seen in hypertrophy research over the years. For example, there is a paper from ages ago showing that one set done 3x a week appears to generate a better growth response than three sets done 1x a week. Many assume this research is a test of training frequency, but other frequency papers with higher volumes don't necessarily draw the same conclusions (possibly because 3x a week is too high a frequency when the number of sets is > 1). It could also be that each set in the three times a week condition is more effective because it's done under conditions with less fatigue. I bet it's both.

Anyway ...

It doesn't matter if it's 8 or 5 or 4 per se, although I'd love to see some deeper research into this because I bet it makes a lot of the squabbling around optimal training intensity or volume or proximity to failure go away.

All of those things can be explained away with the theory of stimulating repetitions.

How Many Stimulating Reps Per Muscle Group Per Workout?

Per Week?

I'm even fuzzier on this, but I'll try to elucidate some of my thinking into something logical here.

Wernbom has a (now) famous meta-analysis from 2007 that led to a rough conclusion that optimal training volumes were:

- For the quadriceps: ~40-60 total repetitions per session.

- For the elbow flexors (triceps): ~42-66 total repetitions per session.

- This data seems to equate to roughly 4-6 sets per muscle group per session. Given that most of the studies are roughly around 10 reps a set.

- This range showed good rates of cross-sectional area increase for both quadriceps and elbow flexors.

- It is important to note that these are isolation exercises, and you might have to account for compound movements that target more than one muscle group differently.

- This data seems to equate to roughly 4-6 sets per muscle group per session. Given that most of the studies are roughly around 10 reps a set.

- The optimal training frequency suggested was 2-3x per week.

- Let's assume that 3x a week is likely only doable when you're a beginner/untrained, or you're training one small muscle group in isolation, or the volume of training is on the low end of this spectrum (4 sets). 4 x 3 = 12 sets/week.

- I generally tell people 2x a week is the sweet spot (1.5x/week maybe, if you're over 45-50) for resistance training, but even 6 x 2 = 12 weeks/week

There are a lot of caveats with this meta-analysis, and it got a lot of criticism back in the day that I don't want to get into here because none of that is the point. The rough figures it suggested have held up.

- Another meta-analysis in 2022 suggested that 12-20 sets per week was the sweet spot

- Note that this included compound movements and seems to have counted 1 set of bench as 1 set of triceps (see my point above). All I mean by that is that it's possible the numbers above 12 are because you need more compound work to equate to localized isolation stress.

- This meta-analysis in 2016 suggested that it's 10+ weekly sets (but didn't get more specific)

- This narrative review shared the same sentiment of 10 or more sets per week.

Now there are probably more but the important thing to note is the trend. I've seen 10-20 thrown around a bunch (although I'm having a hard time parsing my hard-drive for where that number may have come from)

The important thing is that they all roughly show the same thing. More than 10, but less than 20. Let's call it 12 (that's the number I settle on the most) per week, or 6 per session if you lift twice a week, which I'll call the sweet spot.

This matches up with my rough assertion that doing more than ~5 sets of the same exercise is pointless. That's loosely based on a paper analyzing 10 sets of 10 to 5 sets of 10 and finding that 5 sets led to the same (or better) result.

If you assume about 5 effective reps per set, you're looking for about 25-30 effective reps per training session, spread out by about 72-96 hours of rest between efforts.

And this matches up with good real-world routines that I've seen. Hypertrophy Specific Training, Doggcrapp (which is a rest pause method), maybe Myo-Reps, a bunch of Generic Bulking routines and so on and so forth.

I bet if you tried to equate most of these, you get somewhere between 20-30 effective reps per muscle group per workout. If you consider that isolation work is counted a bit differently than compound work. That some of them advocate for reps left in reserve, or that some advocate for training to failure.

This theory just seems to make all the debates about "the best routine" melt away, and nobody but a handful of coaches has seemed to notice?

Why This Matters

For one, it's indicative of the type of training you need to do to grow.

Well, this combined with progressive overload (I'll write an article about that some day), which is just adding weight over time to an exercise in a given target rep range. Note that adding a rep is also roughly equivalent to increasing the weight by about 2-3% in most models.

You either need to be on the heavier side of the typical "hypertrophy training zone" so that the weights you're using would force you to stop by about rep 8. e.g. 5-8 reps.

Or you need to train right to failure, the literature suggests the further from that 5-8 zone, the closer to failure you need to be.

You need to get your training within some proximity to failure, regardless. However, you also need to factor in fatigue.

The more training you do to failure, the more fatigue you generate. So if you're going to train hard once a week, you might want all those sets to go to failure because it's going to be a long time before you stimulate those muscle fibres again.

If you're going to train multiple times per week, then there is likely an inverse relationship between training to failure and the number of training sets you do. You can't do too many sets in a training session or a given training week when you take them to failure.

If you're far from failure, you'll need more volume (# of sets). If you're closer to failure or right at it, then you can probably only do a few before fatigue outweighs the productivity of that training session.

You might think that, based on the above, 5-8 is the best rep range for growth, and I'd tend to agree with that as a general rule. Mostly because you wouldn't have to train to failure, which means you can modulate fatigue better.

However, not everyone can tolerate that rep range well. Not all exercises tolerate that rep range well.

Likewise, if you're outside that rep range, not all exercises tolerate being taken to failure. Complex technical and compound training exercises like squats or deadlifts, or bench press, shouldn't be trained to failure, so ~5-8 reps for those are ideal. If you can't train them in that range and you can't take them to failure, then you might need to make up for that with additional training volume.

It's all related.

This concept is important for you to understand a lot of nuance in other training concepts. It also highlights an approach to training that appeals to many trainees trying to gain muscle, see points above about relative volume, intensity, exercise selection, etc ...

The Sweet Spot Rep Range

Understanding the effective or stimulating rep model helps us paint a portrait for an ideal rep range for growth.

Let me be clear, 1-25 will grow muscle if failure is accounted for.

However, there is a practical implementation of ~5-12 (maybe 6-12, sometimes I think it could be 5-15, these are more similar than dissimilar).

Here is my rationale ...

Time Investment

The biggest potential problem with anything lower than 5 repetitions for muscle gain purposes is accumulating enough effective reps in a reasonable time frame.

It would take 5 sets of 3 to accumulate the same effective volume as 3 sets of 5. Accounting for the necessary rest intervals and the 2 extra sets, it could take 66% more time to get 5 sets of 3 completed.

If you do that for several exercises, suddenly your hour workout is almost 2 hours. There is an upper limit to how much time most people are willing to spend or can spend training.

Also, a point of diminishing returns for that time spent. Doing four exercises of 5 sets of 3 will likely be pretty counterproductive at some point.

You could try to save time using a paired set approach like my twin pairing training system, but at this intensity, you'd likely struggle with adequate recovery, especially with compound lifts and the number of sets would have to be minimized. Otherwise, you'd run into recovery issues.

You'll indeed get stronger doing 5 sets of 3, but you don’t get a better payoff for muscle hypertrophy than the faster 3 sets of 5. Choose your battles, pick the goal that matters most to you.

On the flip side, doing lots of high-repetition work – classified as >12 reps or maybe >15 reps – requires completing a ton of ineffective reps before you get to the effective reps. And the number of sets has to be similar, you can't do 2 sets of 25 expecting similar gains to 5 sets of 10, despite the same amount of work getting done.

3 sets of 20, theoretically takes 100% longer to get through than 3 sets of 10. And 12-15 reps in that 20 are likely 'ineffective.' That isn’t to say that 3 sets of 10 is better, just that it requires less time investment.

That you have to do all that extra work to get the stimulating reps just kills your time efficiency with the training.

Just as there are good reasons to occasionally do sets of 3 (more joint stress, improved strength outcomes, bone density, tendon development).

However, I don't program above 15 reps very often, only in specific situations, like when my client wants secondary muscular endurance adaptations.

It baffles me when I see hypertrophy programs with 20 or 25 reps – unless it's a calisthenic workout. Choose your battles. The goal is to keep the goal the goal.

If you want to improve fatigue resistance and increase muscular endurance, go for it and ramp up the reps. If you want to build strength, you're going to have to spend some time under 5 reps. If you want to build muscle, I strongly recommend trying to keep things under 15 reps most of the time.

The latter should only be a problem for folks trying to use callisthenics exclusively for muscle gain purposes. If you can, find a way to load these for your own sake. It could be a backpack or a weight vest, but something ...

Summary

To trigger growth, you need to generate mechanical tension on muscle fibres. You can do this in one of 2 ways:

- Use heavy weights (something you can only lift 5-8 times before you have to stop

- Train to a point of failure within reason (using a weight you can't lift more than ~25 times)

Each of these approaches should generate several stimulating reps of about 5±3.

Do this for about 4-6 challenging isolation sets within about 1 rep of failure per muscle group per training session, twice a week, and you should theoretically accumulate about 20-30 effective reps per training session or 40-60 per week.

Some people have suggested that compounds be counted at 1/2 of an isolation lift or sometimes even 1/3, depending on the lift. I think it kind of depends on the person, their technique and how they approach the training. Bench pressing for me will probably be proportionately more tricep, but it could be proportionately more chest with a wider grip and more adduction.

I dunno, I don't think there is a right answer here necessarily, I'm just guessing that if certain muscle groups blow up for you with a compound lift, that you might be biased well for that outcome. In another example, my arms don't grow well with back work (I have a 6'5" wingspan for context), but my back will blow up.

I suspect if you dig into your own tendencies for training, you can discover some of your own unique tendencies. I don't like training any pressing wide because my shoulders get cranky. Maybe your back gets cranky during squats or deadlifts so it's not the leg stimulus you hope for.

I could probably list hundreds of examples if I had the time, but the point is I don't know how to count compounds, and you might want to count them differently if you're using them.

If you want to grow optimally, I'd try to get the majority of my training between 5–12 reps (maybe 6-12, maybe 5–15, kind of depends on my mood that day) is where most of a person’s training should lie if muscle growth is the ultimate goal.

It’s the best bang for your buck. The most time-efficient rep range, requiring the least number of total work (sets x reps) for reaching an appropriate number of effective repetitions.

All without the pain of learning complicated technical exercises for the next year – i.e. 1 arm push-ups are considerably harder to learn than simply adding 1-10 lbs to a lift.

Think of this as the most economical way to train if you want, rather than the most ‘effective.’

If you want to build muscle but like lifting heavy, you might want to skew more to the 5-8 rep range. I'd say compound training benefits from this rep range a lot, typically but you don't need any of those to grow (contrary to popular internet lore).

If you're training more isolation lifts or like to feel more of a pump – not that the pump matters – then you might want to skew higher to the 9-12 rep range. They will likely yield similar overall muscle growth, but you may enjoy one or the other more or less.

I currently suspect the minimum effective dose to be about ~5-10 effective repetitions per exercise or muscle group, roughly 1-2 hard sets depending on your proximity to failure. I also suspect that you need to try to lift more than once a week with that, otherwise you've lost something by the time your next low volume training session comes around.

Volume and frequency are inversely related more often than not. Although proximity to failure and intensity all have to factor into the mix too.

I tend to program 2-5 sets per exercise, for ~1-3 (most often 2) exercises per muscle group and shoot for about 12 "technical failure sets" per week per muscle group (meaning 1-2 reps shy of failure). You could train closer to failure, I think, with less and further from failure with more and probably get to a similar place. I'm a moderate, I want to see what lower volumes do first and how an individual handles it before I ramp the volume up.

You’ll periodically want to mix in some low rep training if you are stuck with progressing a weight, or you want to improve strength and joint stress tolerance (bone mass/ligament/tendon development). Mix in some higher rep training if your joints get cranky (~12-15) or even higher if you want some muscular endurance.

I'd suggest that ~80%+ of training time should be moderate load/moderate volume training if muscle hypertrophy is the main objective.

You also have to make sure the sets last long enough, witness a physical slowdown and keep all your work sets within ~4 reps of absolute failure. Hence, my technical failure recommendation.

Depending on what other physical qualities are important to you (strength, speed, power, endurance, etc).

If you’re not getting the result you seek after months/years of training, then a lack of stimulating reps could be one very good explanation. Take it under advisement.

Although the bigger hurdle for most is a lack of progressive overload, which is a topic for another day.