What are Training Deloads? When, how and why should you do them?

Typically, it involves reducing one of the key training elements (intensity, volume, frequency, proximity to failure, exercise selection) to dissipate fatigue and promote recovery. Or sometimes just to address boredom and other elements in the psychology of training.

It's done primarily to peak for competition(s), overcoming training plateaus or more simply as a break.

If you're highly consistent with your training, you can plan them based on your typical training cycles, or most people will do them reactively when you get sick or life otherwise gets in the way.

Most casual trainees don't need to know much about this, as deloads tend to work themselves naturally into the training.

You get sick and take several days off or maybe even a week or two.

You go on vacation. You have work trips. Life gets in the way and bam! You have an unplanned, or unprompted, deload, and it's all about getting back on the horse as quickly as you can to prevent too much of a loss in fitness.

But even casual trainees can find themselves spinning their wheels after a few months of consistency, and so it helps to know what deloads are and how you might use them.

Hint: It depends on your goal(s).

This post was motivated by an intriguing online rhetoric I've been seeing all over the internet about deloading and some new pervasive assumption: That if you're program is planned well, you shouldn't ever need one.

Or something to that effect ...

I can see why this is appealing, especially on an ego level; It's easy to think that your superior planning approach would negate their need. The reality is that no one can do the same thing indefinitely and find success indefinitely, and changing programming variables is a deload on some level.

It's just moving the goal posts on how they are implemented or baselessly criticizing how they are classically implemented.

And training reduction that happens in any manner is essentially a deload. Your body doesn't care about formal definitions or fancy new definitions. All athletes deload. All semi-serious trainees have to deload, even if they'd rather call it a taper.

So I'm going to clearly define what a deload is and hopefully briefly discuss a bunch of ways they can productively be implemented.

What is a deload?

Broadly speaking, deloading is a reduction in training. Yes, typically to allow for recovery and adaptation, and typically implemented between training blocks. But on the surface, it's just a reduction in one or more training elements or components.

They can be:

- deliberately planned – e.g. every 8 weeks

- reactive: follow a rules-based implementation – e.g. y lift stalls out for more than x time frame

- reactive: sporadic and unplanned – got sick, went on last-minute vacation, had to travel for work, kids are sick, etc ... etc ...

I think a lot of the confusion I see online stems from some presumed strict definition of it having to be planned or it being the outcome of a presumed want/need.

I don't care how good your programming is, everybody takes time off and everybody stalls on programming eventually. If maintenance is the goal, that's another thing entirely, but ...

If you have to take 5-10 days off training, whether you planned to or not, you deloaded the body over that time frame. Another example: Work (or school) has been crazy this week, and you inadvertently skipped some workouts or rushed through some, lowering your typical frequency or training volume.

Even mild changes in programming will amount to being a deload because learning new exercises takes learning a new skill, which results in less weight being used, even if the training volumes stay largely the same.

You may not have wanted to or planned to, but you did. You reactively deloaded based on your current situation.

All of these things can be considered a "deload," so let's just ignore the pedantism.

As I indicated earlier, for most casual exercisers, planned deloads tend to be unnecessary. Life just has a way of happening, and they will work themselves into the process, whether you deliberately tried to or not.

Why deload?

If they don't have a way of magically working themselves into your routine, and you are more serious about your exercise or more consistent than the average gym goer, then there are legit reasons to consider deloading purposefully. Either in a planned manner or reactively based on training outcomes.

Given that the primary purpose of a deload is to allow for the dissipation of accumulated fatigue from previous training. This serves several purposes:

- Breaking Through Plateaus

- Get skilled enough at something, and progress will stall. A deload can allow you the opportunity to build back up and overcome a plateau.

- Peaking for Competition

- This is typically called a "taper." It's a brief reduction in training (usually 5-10 days, depending on the person) ahead of an important competition so as to reduce volume and/or frequency, sometimes adjusting intensity, in order to optimize performance for a new personal best in the competition.

- Changes in priorities or goals

- You might not want to be lifting for size or aesthetics all the time or even all year. Maybe you decide to pick up a new sport. You might get bored with training a particular lift or what to prioritize, some other skill, or physiological adaptations.

- Significant life events

- You get married, get pregnant, adopt a child, volunteer, buy a house, move across the country, start a new job, change careers, go (back) to school, find a new partner, renovate a home, etc ... etc ...

- Simply Scheduling or Taking Breaks

- Honestly, sometimes your body (and mind) just appreciates a bit of a break even in the absence of major life events or big changes in goal(s). All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy. Very often, this is just starting a new training block and mixing up the patterns or tools you use; a lot of people eventually just get bored and crave something new.

Imagine if all you did was work, work, work. Admirable. I'm sure you know some people like this. But research continually shows that vacations benefit workers. That is in part why employers have basic policies around this and why most developed countries institute statutory holidays and other mandatory vacation allotments. Deloads are similar.

Work + Rest = Success.

It's a balancing act. Rest too much and you're probably not doing enough work to get a good stimulus for your goal(s). Work too much and you're not resting enough to recover from that work or to stay fresh so that you can keep progressing towards your goal(s).

But also life changes. You grow and evolve as a person. Priorities shift. What you cared about in your 20s might not be what you care about in your 80s.

When should you deload?

I hate to beat a dead horse, but you might not ever need to plan when. If you take a vacation quarterly, take it. If you've young kids in daycare, you're likely to get sick several times a year already.

If your goals are health or well-being related or maintenance-related, you may never really require a deload; however, the training likely isn't so stressful or progressive that it's pushing you into a state where a deload is necessary to achieve these goals.

Broadly speaking, I'd consider it under the following conditions:

- Joints feel chronically achy

- Fatigue and the desire to sleep become chronic

- Illness

- Psychological burnout or serious boredom

The above applies a lot to more recreational and less serious trainees.

Even in the context of a fat loss goal, I'm not sure you need to deload beyond those markers because, depending on the energy deficit, you might not want to have an excruciating exercise regimen in the first place. You're probably just aiming to maintain lean mass and doing some light cardio. Taking diet breaks is likely more critical to that desired outcome.

The problem with reactive deloads, however, is that there is a group of trainees who don't listen to their bodies very well. It requires a certain level of restraint and a certain level of self-awareness. People who recreationally push themselves hard likely benefit from a break at least once a quarter (every 12 weeks).

You likely only need to plan deloads for the following goals:

- Athletic performance matters to you

- Strength matters to you

- Muscle growth (hypertrophy) matters to you

- You're constantly injured or having to stop training for some physical reason

The last one is simple: take a break every 8-12 weeks and take a good, hard look at your program. It's probably too much for you in some capacity.

The first one is very dependent on the competition schedule and the sport. I couldn't write a book that would go through every possible scenario I've had to program through or heard about. So I won't do it justice here.

If you're in a sport that only has a handful of big competitions per year, you're likely tapering (which is effectively deloading) for those competitions. This is true of a lot of strength sports (Olympic lifting, strongman, powerlifting), endurance sports and track & field sports.

If you're in more of a mixed or power sport, it's about working with your coach to monitor your training status in a more proactive way. Things like sitting out games (if needed) or at least not playing full-time minutes. Planning around hard schedules like double headers or tournaments. In season, you're general preparation training (resistance training/cardio) is probably minimal to more like maintenance. Unlike the sports mentioned above, most of your general prep ends up being done in the off-season, rather than between competitions.

The two in between, however, are relatively easy:

- Hypertrophy - Roughly every 8 weeks

- Strength - Every 12 weeks at the longest

If you'd like a little more nuance than that, deloading may also depend on your training status:

- Beginner Status (you can make progress every ≤2 weeks)

- Intermediate Status (you can make progress every 3-7 weeks)

- Advanced Status (you can make progress every 8-12 weeks)

When Advanced Trainees Should Deload

Let's start with advanced and work backwards because this gives you a baseline for consideration. If you've trained progressively and consistently with a challenging program (i.e. it wasn't maintenance or once a week, or very low volume training) for 12 weeks, it's probably time to deload. Regardless of your goal, whether it's growth or strength.

Of course, context matters; high-volume training or purposeful over-reaching might not make it this long. The programming matters, but assuming a sensible plan, always plan to switch things up after 12 weeks. If your goal is more hypertrophy-oriented, 8 weeks could also be your threshold because the weights are likely to be moderate and will stall long before you hit 12 weeks. You're probably not going to back-cycle growth the way you would with a strength goal.

That said, if you're advanced, you're also more likely to be running a specialization cycle. Specialization cycle volumes for one or two muscle groups are probably high. I'd skew more to 8 weeks for this. Strength requires practicing the movements, so the longer 12-week cycles tend to work better once you reach certain levels of strength.

When Intermediate Trainees Should Deload

You could wait 12 weeks, but given that you probably aren't lifting as heavily as the advanced trainee, and you can still make meaningful progress in shorter training cycles, you probably don't need to. You're probably not getting a whole lot extra out of those last 4 weeks.

Most of my clients end up in this range, and so technically speaking, many of them benefit from 8-week cycles (if they can tolerate the boredom), followed by a deload. Even if they have strength goals, they likely won't be able to stretch an effective 12-week cycle out quite yet. Anything less than 8 weeks tends not to be enough practice for strength movements nor enough of a continuous stimulus for growth.

When Beginners Trainees Should Deload

See my original recommendations for recreational lifters.

I really enjoy working with this group, because it's a period of so much personal discovery. However, they probably don't need to deload until they reach intermediate status. Progress during this phase will appear linear for quite some time (6+ months), depending on the starting point.

I just don't think deloading is as important until progress stalls and the weights moved are meaningfully challenging.

That said ...

8-12 weeks is possibly still a good recommendation across the board. You may not physically need a break/deload when you're a beginner, but you may benefit from a mental one.

How to Deload?

Deloads can be implemented in several ways, but here is a brief list of the approaches I think have the most value in the rough order that I use them, although you can also combine them a bit:

- Volume Deloads

- Intensity Deloads

- Exercise Variation (Deloads)

- Frequency Deloads

- Stability Deloads

Volume Deloads

Here, you reduce the number of sets you're doing while maintaining the intensity (weight used on any given exercise) and the proximity to failure.

My preference is halving the volume, but it can be a bit fluid. How do you halve 3 sets? If you have 4 sets prescribed for an exercise, drop the volume to 2 sets. If you're doing 3 sets, you could go to 1 (or 2). If it's a lagging muscle group or lift, consider 2 over 1 in the case of 3.

But it's better to have a bigger picture understanding of the whole program so that the deload looks something like this:

- Week 1 = 50% of the previous (or typical) volume

- Week 2 = 75% of the previous (or typical) volume

- Week 3 = Right back into the thick of things at typical volumes

I am more likely to use this method with hypertrophy-oriented outcomes because it's dead simple to implement. This also benefits individuals who prefer training to failure (or very near) or who struggle with submaximal efforts or using intensity deloads.

Intensity Deloads

In this type of deload, you reduce the weight on the bar while maintaining volume, rep ranges and frequency, but your proximity to failure drifts downward accordingly. I only ever do these with people who have strength-oriented objectives, who have exercises programmed for 5 reps or fewer, and only for those strength-oriented lifts.

You don't have to do them like that, but for moderate to high rep range exercise choices, I find that volume deloads are better (hence my comments about combinations).

Typically, I drop the weight used by about 15-20% from someone's previous best (PB) number, or PR = Personal Record. For example, if you're PB in a lift is 400 lbs for a double, then we're going to drop the weight down to 80-85% of that, or about 320-340 lbs for a double.

If you noticed that's a lot less than 400 lbs, well, it is. Very few people are this strong to begin with, and I chose it because it's an easy number to work with. There is more trial and error involved in this method.

320-340 in this context should feel like butter going up. It should almost feel like a waste of time, that's how easy it should feel (but it isn't, remember it's allowing recovery to happen, especially on the joints in this context). It should feel pretty easy for the first 2-3 weeks of a new cycle until the weights creep back up into difficult territory. You don't want to grind strength work often unless you're attempting a PB/PR.

In practice, it might look like this:

- Week 1: 320-340

- Week 2: 340-360

- Week 3: 360-380

- Week 4+: 380+ and shoot for a new PB (402.5-405 maybe) at the end of the cycle (week 12).

Again, you will need some more trial and error with this method, but over the last 9 weeks, the bumps in weight have gotten smaller. Some people benefit from longer ramp-up periods, others from shorter ones. Some people benefit from smaller drops (10-15%) than others, but 20% seems to be about the max you should consider if you're strong enough to make this work for you.

Novice powerlifting programs like Starting Strength also follow this kind of approach, which seems like a big lift (pun intended) for novices, but that's just me.

Generally speaking, if you hate math, don't use this method. Or hire someone to do it for you. 😄 There is more nuance to it than the volume method, so I don't recommend it as much publicly, but because I'm the one handling the programming privately, I still use it all the time.

Exercise Selection Deloads

Any time you change an exercise to something you haven't done (ever or recently), there is a motor learning element involved. The motor learning element initially lowers the intensity someone can use on that new lift, even when it's similar to something they were already doing.

For the casual trainee, this should probably be your typical strategy. Although I like to combine exercise changes with volume deloading to combat the potential soreness of new exercises.

Basically, when you do too much training volume, with new exercises (especially eccentric-oriented exercises), too close to failure, you open the door for soreness. Being sore tends to lower the quality of your subsequent workouts, so it's something you want to manage and minimize. Although no one eliminates the potential of it entirely.

In a nutshell, you're going to swap some or all of the exercises out to varying degrees, you might play with the exercise order, but the intended intensity and proximity to failure are going to remain about the same. You're going to reduce the typical volumes back to 1-2 sets for any new exercises and add a set back each week until you get back to typical training volumes for that muscle group or movement pattern (push, pull, etc ...).

As examples, low incline pressing instead of flat pressing. High incline pressing instead of overhead pressing. A different grip row or pulldown. Plate-loaded machine with a different resistance profile instead of a stack-loaded one. Front squat instead of a back squat. Etc ... etc ...

Depending on your goals, you don't need to change the exercises much (if at all), but in my experience, a lot of people benefit from this approach mentally. Especially if they don't have an exercise-specific long-term goal.

You don't want to go too nuts with this too often. You can think of this just as a tweak or change in the program, and then you follow a sensible volume ramp-up. The degree of that change is up for debate, depending on the individual in question, because you have to take into account:

- Training equipment access

- Familiarity with the exercise

- Skill with the exercise

- Goals

- Injury history

- Results of the previous training cycles

- Anything that possibly made joints cranky in the past

I think if you want broad generalized fitness (and most people do), this is the best way to approach things, but it doesn't work well for specialization. This is how I'd approach "deloading" with beginners. It's often just about exposing them to more motor patterns in the early days, so they can figure out what they like, what they want, what works for them, and then the training gets a little more boring beyond that.

Trainees in strength or endurance sports or maintenance programs in the sports performance world. Powerlifters have to deadlift, squat and bench press, so you can't take those out of the program entirely. Olympic lifters have to do the Olympic lifts and so on. Runners have to run. Cyclists have to cycle.

For people with those goals, you can only do this with accessory or general prep movements, and even then, if the accessory movements are working, you may not want to tweak anything. If it ain't broke, don't fix it.

Frequency Deloads

This one is pretty simple; you just reduce the number of training sessions per week. In a pinch, like vacations or sickness, these tend to work themselves out all on their own.

The problem is that once a week is kind of the minimum frequency that works, and most of my clients only repeat the same exercises or train the same muscle groups 1.5-2x a week already, so it's really just dropping some training days. If you're not at 2x a week already, it's probably not worth your time.

I only mention this one because I like it when people are doing damage control (life gets in the way of their desired training frequency) or moving between active goal pursuit and maintenance. But even in this regard, it's more like starting an entirely new low-frequency training program, but it can be good for brief periods in a pinch if you don't want to lose too much fitness between a long trip or a significant life event.

Stability Deloads

This is a fun one, more movement-oriented than strength or power or growth oriented. I don't use this one for serious trainees much, it's more of a short-term cure for boredom and certainly only for athletes who have some kind of prehabilitation concerns or return from injury or stuff like that.

It's more about the mental break if I'm being honest, but it also creates this new challenge for the trainee for 1-3 weeks.

Destabilizing an activity naturally lowers the weight you can use, but it also increases cognitive focus and attention. In my case, I'm not talking about throwing you on a BOSU ball for everything or standing on Swiss balls. I don't think that has much value, and even thing has questionable value.

Some ideas:

- Single-arm dumbbell press instead of a 2-armed version

- A quadruped row instead of a more stable row

- Single leg squats/step-ups (especially unilaterally loaded)

- Single-leg hinges (especially unilateral loaded)

- Kettlebell or dumbbell loaded exercises instead of machine or barbell

Doing this isn't great for strength or power or growth, but it can help identify some imbalances and address movement areas or smaller muscles that easily get ignored. It usually feels good, but I'd caution you about making it a staple approach.

I'm far more likely to recommend using a few of these exercises as warm-up exercises than to dedicate significant volumes of training towards them. These exercises tend to make you feel good in the short term, mostly because the weight you use is a lot less.

Summary

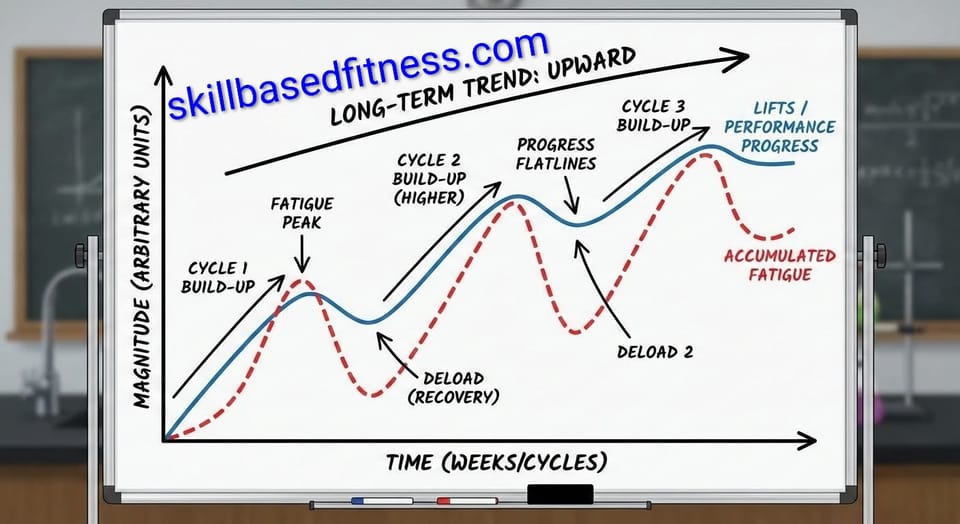

Deloads do not directly stimulate strength or hypertrophy; instead, they facilitate continuous progressive overload by allowing the body, mind and connective tissues to recover.

Progressive overload in the long term is the most important variable for developing strength, growth or power.

Without them, trainees eventually hit plateaus, regress, suffer injuries, or experience psychological burnout. This is particularly true for those training with sufficient volume and intensity to stimulate growth.

If you're a moderately serious trainee, or you can easily stay consistent for 8-12 weeks at a time, consider them every 8-12 weeks. I generally prefer volume deloads for growth work and intensity deloads for strength (or power) work.

I gave some other fun or easy suggestions you can also use in a pinch, but changing the programming up itself every 8-12 weeks inherently acts as a deload for the more casual trainee already.

Remember Work + Rest = Success